The Social virtue par excellence

Social virtue

Unity, the social virtue par excellence, is a principle Christ imbued in Christians and takes after the essence of God himself who is one and three Persons. Thus unity lives, by its intrinsic constitution, in the society of the faithful which is the Church, but cannot impact on civil society which is made up of Christians who cannot clash and combat with each other on social ground, when they are in accordance in religious issues. This means that spiritual unity suffices to eliminate the political-economic discrepancies – but that this is lessened and reduced according to their relativity and contingency. Above all, it helps the spirit to reduce also the material differences among them due to the sentiment of solidarity, and the obligation to reach harmony and bear with each other mutually, impeding even civil competition from violating essential charity.

Igino Giordani, The social message of Jesus, New City, Rome, 1966, p.419.

Divisions

Among true Christians, even political parties and class divisions can generate diverse but not hostile viewpoints: even when they belong to different associations and economic levels they cannot – as Christians – forget that they are part of a sole, essential, divine and irreplaceable family, which is more important than all the parties and castes, since it is rooted in the Absolute, and destined to ensure us eternal happiness that surpasses the temporal, momentary, and earthly activity. In short, Christianity models characters according to the principles of concord and fraternity; and these characters act with their spiritual education, even in earthly relationships.

Igino Giordani, The social message of Jesus, cit., p.420.

Charity and unity

Charity is a devouring fire that consumes divisions: passions, errors and misunderstandings, leading spirits towards that same unity which binds the Father to Jesus. In this way human society is created according to the Trinitarian image of the divine society, where three Persons coexist in a God, since they love each other to the point of unifying themselves to one another, while they distinguish themselves to be able to do so. As the Greek Fathers of Alexandria said, division is a sin.

In this manner, while inserting creatures in a sole mystical body of Christ, unity generates a convivial society which, through charity, becomes not only divine but humane, and allows it to coexist on this earth with God, and a sole Holy Spirit binds mortal men and divine persons. It is the climax of religious elevation, and produces the divinization of man who is no longer isolated, but through the brother, is made a «sacrament» of God, in Christ, and Christ in God. It is a chain that leads us to experience eternity with «perfect joy» – within our earthly existence, where death is dead.

Igino Giordani, The social message of Jesus, cit., pp.420-421.

Unity and family

The family is healthy when it is united. Unity is such that it has become a dominant motif of the post-war pontificate and in fact responds to the vital need for a society that would perish if it does not unite. But the same external, social, civil, political and religious unity starts from the family: which for such an arduous task, needs to reunite and nurture unity with the blood of Christ, drawing from the Eucharist, which is the body, blood and divinity of Christ. And unity gives peace.

Igino Giordani, Laity and priesthood, New City, Rome, 1964, p.183.

Plurality and unity

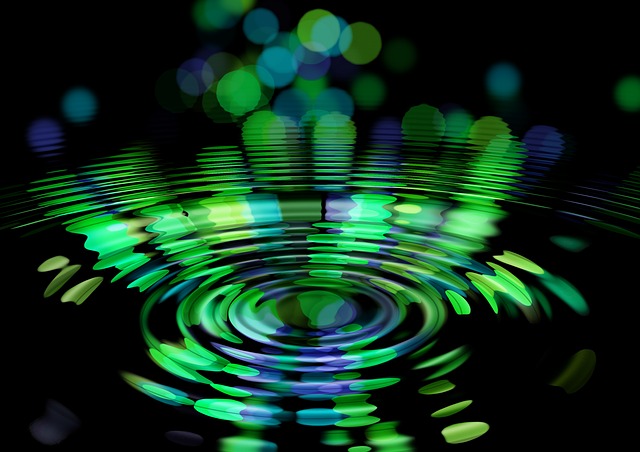

Plurality coexists with unity, and this existence, due to the possibilities of love through the action of the Spirit which blows where it wills, creates a Unitarian and Trinitarian game – like a wave that unceasingly breaks and reunites – which allows to continuously represent and call God himself amid the human drama, operating a mystical mass which, as an extension of the Eucharistic rite in Church, is celebrated 24 hours a day on the streets, at home, in the office, in the countryside, in the market and shops, wherever two creatures unite in him.

Igino Giordani, The divine adventure, New City, Rome, 1993 (1960), p.36.